Introduction

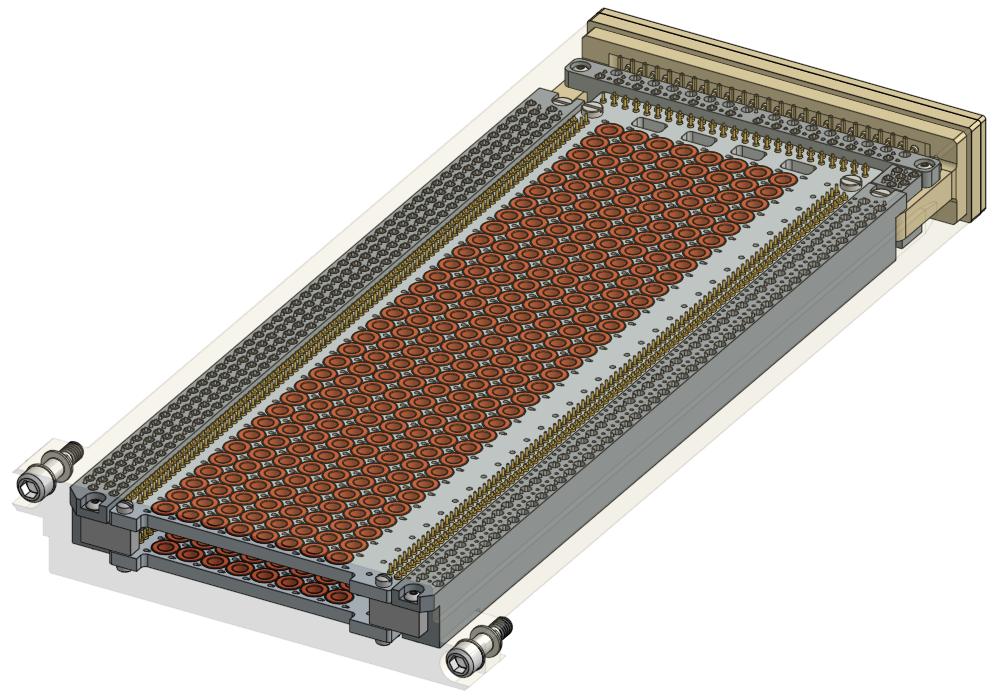

The fixed memory system of the Block II Apollo Guidance Computer consists of 6 physical core rope memory modules holding a total of 36,864 16-bit words. Each module contains 512 cores, which hold 192 bits of information apiece, for a total of 98,304 bits, or 6,144 words. This information is physically woven into the rope module during manufacturing. For any given core, there are 192 sense wires, each of which is either threaded through the core (indicating a 1) or bypasses the core (indicating a 0).

Like regular core memory, the cores in a core rope exhibit magnetic hysteresis -- i.e., they can be magnetized either clockwise or counter-clockwise, and retain this state indefinitely once external magnetic forces are removed. In regular core memory this magnetization stores one bit of information; in rope memory, it is effectively used for addressing.

The cores in rope memory are much larger than their core memory counterparts. They have an outer diameter of about 0.25". Instead of being solid ferrites, they are made with 0.000125"-thick mo-perm (molybdenum permalloy) tape wound around a steel bobbin. This slightly softer magnetic material reduces the magnetic force required to flip the larger core's polarity. Furthermore, the extreme thinness of the tape reduces eddy currents inside the core, allowing the switching to happen faster.

There are two main components of addressing core rope memory: core selection and strand selection.

Core Selection

Magnetic Properties and Basic Wiring

The goal of core selection is to select a single core out of the 512 in a module. This is done in two phases: the "set" phase and the "reset" phase. During the set phase, current is run through a set of wires that cause only the core being addressed to flip its magnetization. During the reset phase, strand select circuits are activated to allow reading of data, and the core is switched back to its original state.

Let's look at the wiring in a single core.

To the left of the core is its hysteresis curve, also called the B-H curve. This diagram shows the magnetic properties of the rope memory cores. The vertical B axis is the core's flux density, measured in Teslas. This is essentially a measure of how strongly the core is magnetized. The horizontal axis is the externally applied magnetizing force, measured in Amps per meter. When no current flows though any wires passing through the center of the core, the magnetizing force is 0, and the flux density of the core will settle into one of the two intersections of the hysteresis curve with the B axis.

To change the polarity of a core from its default "reset" state to its "set" state, a strong current -- 450mA in the AGC -- is run through the core's Set wire. This pushes the core's magnetic flux to the other side of the B axis, to its saturation point. When the set current is stopped, the core settles into a new, reversed, magnetic state. The core can be returned to its original state by running 450mA in the opposite direction through its Reset wire.

For a single core, just these two wires are sufficient. If the Set and Reset wires thread through more than one core, then additional wires are needed to prevent all of the other cores from switching. These are the Inhibit wires, which are also threaded through the cores to carry current opposite the direction of the Set current. Inhibit wires are woven in pairs, with each pair separating the cores into two zones in different ways. Each Inhibit wire carries 225mA when active. The magnetizing force acting on the core depends only on the net sum of current running through it; so if two Inhibit wires are active when the Set wire is activated, the net current will be (-225mA) + (-225mA) + (450mA) = 0, and the core will not switch.

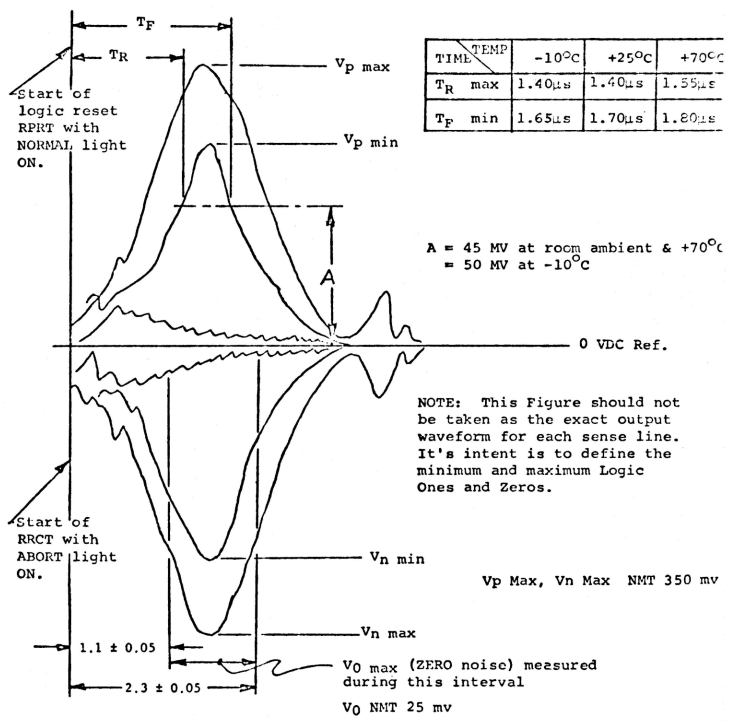

According to Faraday's law of induction, a change in magnetic flux will induce a voltage on wires passing through that magnetic field. In practice for rope memory, this magnetic field acts inside the core on wires passing through it, but not on wires that do not pass through -- even if they are physically touching the core. This is the means by which 1s and 0s are stored in rope. When a core is switched, all sense wires passing through it will have an approximately 100mV pulse induced on them (indicating a 1); any wires that do not pass through the core will not (indicating a 0). Up to 25mV of noise on the sense wire is acceptable for a 0.

You may have noticed from the B-H curve that even when the core does not switch, when a core is pushed into saturation by the inhibit or reset wires, there is still a small amount of change in magnetic flux (i.e. vertical displacement on the B-H chart). This is called the "shuttle flux", which does induce a small (~5mV) "shuttle voltage", and it is a large contributor to the noisiness of rope memories. Luckily this small excursion is fast enough that the sampling window can be adjusted such that is misses the shuttle voltage on the sense wires but captures the slower, larger pulse of the actual switching core.

AGC Rope Organization

The 512 cores in a rope memory module are arranged in two physical 8x32-core layers. The diodes and resistors that form the strand selection networks line these layers on three sides, wired together in a cordwood structure.

Despite the physical arrangement, the cores are logically grouped into four "planes" -- A, B, C, and D. Each layer is divided lengthwise into two 4x32 planes.

All address-related wires are activated or deactivated based directly off of the least significant 9 bits of the FMA (Fixed Memory Address) of the location being read. The address bits correspond to wires as follows:

| Bit | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | IL01 | Activates IL01 during set time if 1, or IL01/ if 0. |

| 2 | IL02 | Activates IL02 during set time if 1, or IL02/ if 0. |

| 3 | IL03 | Activates IL03 during set time if 1, or IL03/ if 0. |

| 4 | IL04 | Activates IL04 during set time if 1, or IL04/ if 0. |

| 5 | IL05 | Activates IL05 during set time if 1, or IL05/ if 0. |

| 6 | IL06 | Activates IL06 during set time if 1, or IL06/ if 0. |

| 7 | IL07 | Activates IL07 during set time if 1, or IL07/ if 0. |

| 8 | RESET | Selects between wires RESETA (0) and RESETB (1) if bit 9 is 0, or between RESETC (0) and RESETD (1) if bit 9 is 1. |

| 9 | SET | Activates SETAB during set time if 0, or SETCD if 1. |

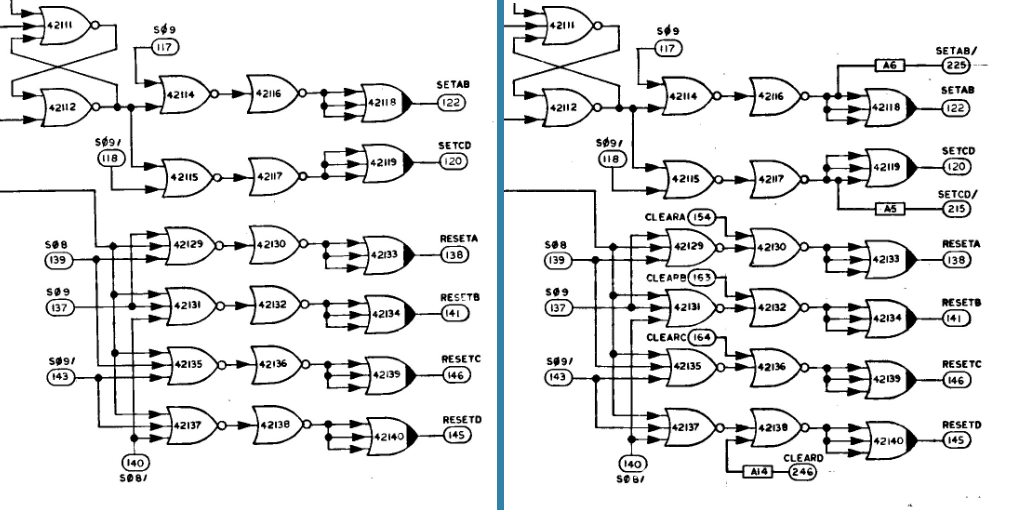

One Set wire threads through every core in both planes of a physical layer. SETAB threads all of the A and B plane cores, and SETCD threads through the C and D plane cores. Each plane has its own dedicated Reset wire threading all cores -- RESETA, RESETB, RESETC, and RESETD. Because the reading is done at reset time, having shorter Reset wires reduces both the impedance of the wire and the shuttle voltage noise from unswitched cores. Because these things don't matter during the set phase, the Set wires can be longer to reduce the number of pins required, so long as the inhibit wiring scheme is sufficient to select only one core out of the two planes receiving a Set current.

Inhibit wiring is accomplished via inhibit wires IL01 through IL07 and IL01/ through IL07/. Each IL0x and IL0x/ split all 512 cores in the module into two 256-core groups in different ways -- e.g. IL01 threads through a group of 256 cores, and IL01/ threads through the other 256 cores. The groups are chosen such that each successive inhibit wire that is activated cuts the number of remaining uninhibited cores in half.

Seven inhibit wires is, of course, not enough to uniquely select 1 out of 512 cores. When one wire from each of the seven inhibit pairs is activated, the total number of cores receiving no inhibit current is 512 / 27 = 4. It works out that these four cores are evenly distributed among the four planes. Because only one of SETAB or SETCD is activated during any given set cycle, two of these uninhibited cores don't matter; they pose no risk for switching because they will not receive any Set current. The core located in the other plane in the same physical layer, however, does pose a problem.

A further issue is that for any given address, there exist a number of addresses that differ by only a single bit. Each one of the cores corresponding these addresses will therefore have only a single inhibit wire active. For these cores, the single 225mA Inhibit current is not sufficient to oppose the 450mA Set current. The net +225mA will apply enough magnetic force to the cores to at least partially set them, which would wreak havoc on future reads.

One additional pair of inhibit wires were added to solve both of these problems: the parity inhibit wires ILP and ILP/. These wires are woven in a more complex pattern, passing through each core based on the parity (i.e., number of 1s) in the least significant 8 bits of the address. Specifically, ILP is activated if the number of 1s is even, and ILP/ is activated if it is odd. With this scheme, it is theoretically guaranteed that the parity inhibit wire will be active in every core whose address differs only by 1 bit. This occurs naturally because two addresses with only 1 bit different will by definition contain different numbers of 1s.

Note that this property also applies to the core that differs only in bit 8 -- i.e., the second fully uninhibited core in the same physical layer as the core being read. When all 8 inhibit wires for a read are activated, then, this core will only have the parity wire active in it. All other cores in the target physical layer will have at least two inhibit wires active. Because of this one core, the parity inhibit current was increased to 300mA. While the regular 225mA Inhibit current is insufficient to oppose the 450mA Set current, the 300mA parity current is. A net -300mA + 450mA = 150mA will not cause any partial setting of the core.

That, at least, was the theory -- but there is a design flaw that wasn't caught until relatively late in the Block II logic design. Recall that while there are only 7 normal inhibit wire pairs, the parity inhibit wire is calculated over the lower 8 bits of the address. With this in mind, consider what happens when an address differs from the target address in both bit 8 and one other bit (1-7). Because one bit associated with inhibit wires is different, one normal inhibit wire will be active in the core. But because bit 8 contributes to the parity but does not control an inhibit wire, no other inhibit wires will be active, including parity. Again due to the bit 8 difference, all 7 of the cores in question will be in the same physical layer as the target core, but in the opposite plane. This means that with the scheme described so far, any time a core is read in one plane, an additional 7 cores will be set in the other plane in the same layer. No good!

By the time this was discovered, it was too late to make significant design changes. In theory, this could have been fixed by increasing the current for every inhibit wire pair to 300mA, such that any single inhibit wire would be enough to oppose the Set current. This would have led to an additional 75mA * 7 = 525mA required for every Set cycle.

The MIT/IL engineers found a better solution, though. Because all 7 of the problem cores will always be in a different plane from the core being read, it is possible to also activate the 450mA Reset wire corresponding to that plane during the Set cycle. This will strongly inhibit all cores in that plane.

With all of this -- 7 inhibit wires, 1 inhibit parity wire, 1 reset wire, and 1 set wire -- one single core in the module is switched from its reset state to its set state during the Set phase. The Reset phase is significantly simpler: only the Reset wire corresponding to the plane containing the switched core needs to be activated. As the core switches back to its reset state, a voltage is induced on all (up to) 192 sense wires threading through it.

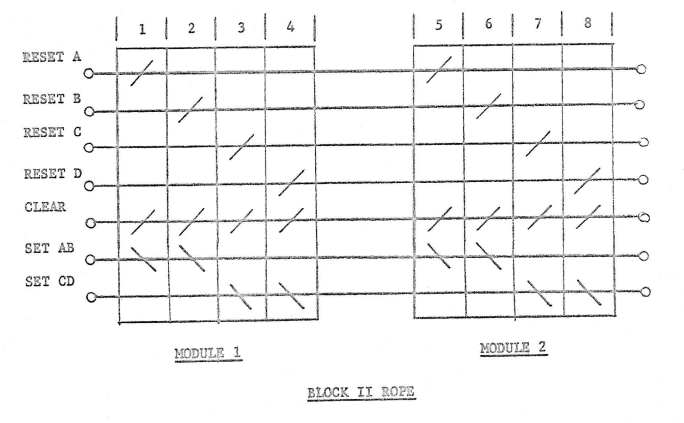

There is one final wire related to core selection that we haven't discussed. Since the Block II AGC reads data from rope memory at reset time, a significant amount of time passes between when an address is first determined and the data from it becomes available. Because of this delay, the rope memory cycle is actually started in the preceding instruction, before the instruction accessing the data is fully decoded. It is possible for various reasons (interrupts, counts, quarter-code instructions, etc.) that a rope cycle needs to be aborted after it has been started. By the time this happens, the Set cycle has already been completed but the Reset cycle has not yet begun. To simplify recovery from this state, the CLEAR wire is threaded through every core. Pulsing 350mA through this wire guarantees that whatever core got set is reset, without any additional logic required.

Core selection is now complete, and it is the job of the strand selection circuits to down-select these 192 sense wires down to the 16 corresponding to the memory location being read.

Strand and Module Selection

The strand selection circuitry is comprised of two parts: strand selection and module selection. The need for strand selection is obvious given the discussion so far; the desired data for any address is located on one of 12 sets of 16 sense wires. So far, however, we've only looked at what happens inside a single module. There are six such modules installed in the computer, logically organized as three pairs. All core selection wires are connected in series between each pair. As a result, the Set cycle actually sets two cores -- one in each module in a pair. There therefore must also be a mechanism for selecting between the two modules, in addition to selecting one of the twelve strands.

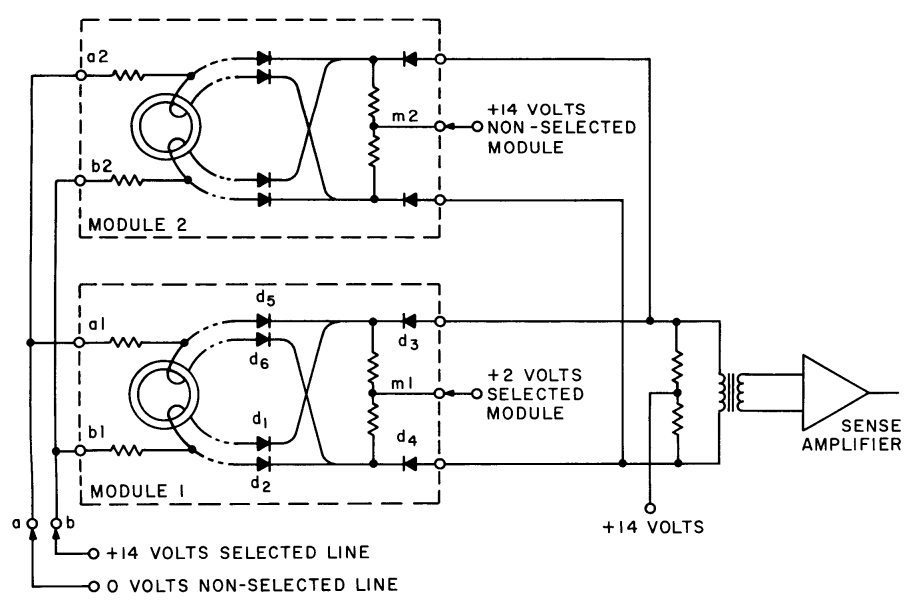

Both types of selection are implemented as resistor-diode networks, and operate under the same basic principle. All diodes are situated in series with the flow of data on the sense lines. To select a particlar module, and to select a 16-bit word out of the 12 available from that module, the addressing logic of the computer applies voltages to strategic points of these networks such that the desired path is the only one in which all diodes are forward-biased. These forward-biased diodes will pass the voltage blip from the switching core, while all of the revserse-biased diodes will block the signal. For the following sections, refer to Figure 6, an explanatory diagram from MIT.

Strand Selection

The strand selection networks are relatively straightforward. There is one input pin on each module for each strand, to which voltages are applied for selection. All pins for the same strand are wired together for all six modules. In Figure 6, these wires are labeled a and b, connecting pins a1 and a2, and pins b1 and b2, respectively. These strand selection pins are connected to the sense lines through a series of resistors, which pull the sense lines associated with that strand to the voltage applied to the strand selection pin.

In Figure 6, strand a is deselected, and all pins connected to it are pulled to 0 Volts. Diodes d5 and d6 will thus always be reverse-biased, regardless of what voltage is applied to the module selection pin m1. While reverse-biased, these diodes will effectively block all signals coming from a switching core. Meanwhile, strand b is selected by application of 14 Volts. Diodes d1 and d2 are then forward-biased, and will cleanly pass through data to the next stage of the circuit. This circuit is duplicated for all 16 sense wires in all 12 strands -- so after this stage of diodes, we are down to only 16 wires which contain the data for our target strand.

Module Selection

An additional stage of diodes selection is used to connect the sense outputs from only the one desired rope module to the computer's sense amplifiers. The means by which this happens extremely unintuitive. Like strand selection, the module selection diodes will only pulses through when they are forward-biased. Unlike strand selection though, the data appears to go backwards through these diodes to exit the module. Diodes are not known for passing current backwards, and the breakdown voltage for the diodes in question is no less than 70 Volts -- so it is not immediately obvious how the 100mV pulse from a switching core makes it through.

Each module has one module selection pin, shown as nodes m1 and m2 in Figure 6. All unselected modules have 14V applied on this pin. This keeps diodes d3 and d4 reverse-biased, so no pulses are able to escape the module, even on the selected strand.

The selected module is connected to a 128mA constant current source, which is simplified to 2 Volts in Figure 6. This forward-biases d3 and d4, allowing pulses to exit the module and make it into the computer's sense amplifiers. The means by which data makes it through these diodes is illustrated in Figure 7.

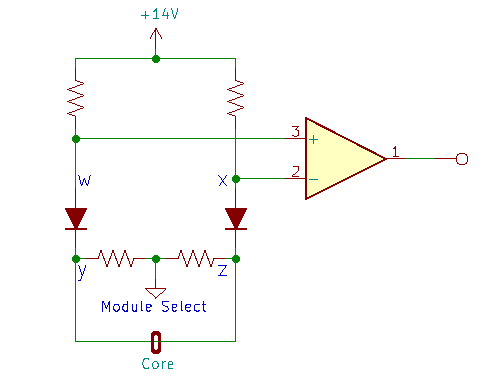

Normally the core has no effect on the wire passing through it, so nodes y and z are shorted together and at the same voltage. Both diodes are forward-biased, and so nodes w and x are also at the same voltage, approximately 0.6V higher than nodes y and z. The differential amplifier connected to these wires will see no difference, and will output a 0.

When the core switches, approximately 100mV is momentarily developed between nodes y and z. Since both diodes are forward-biased, they will maintain a constant forward voltage drop of about 0.6V. Nodes w and x will therefore also develop a 100mV difference. This is enough to be detectable by the differential amplifier as a 1.

Note that because this is a differential measurement of a transient pulse, all of the diodes must be dynamically well-matched pairs. Additionally, because the forward voltage of a diode depends in part on current, noise on the voltage rails involved in strand and module selection could potentially erroneously be detected as data if the diodes respond differently. The use of a constant current source on the module selection pin mitigates this concern.

References

- Digital Development Memo #219: Core Rope Memory Selection, Block II

- Digital Development Memo #239: Block II Rope Memory Circuits and Timing

- Apollo Block II and LEM Computer Design Review

- JDC 04255: Fixed Memory Test

- R-500: Space Navigation Guidance and Control, Volume II

- ND-1021042: LEM Primary Guidance, Navigation, and Control System Manual, Volume II

- SCD 1006320: Core, Magnetic

- 2005017: Inhibit Wiring, Fixed Memory

- 2005935: Schematic, Fixed Memory Module B1-6

- 2005938: Schematic, Rope Driver Module B16-B17

- 2005926: Schematic, Strand Select Module No. B15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| State: | |

| Net Current: | |

| Active Wires: |